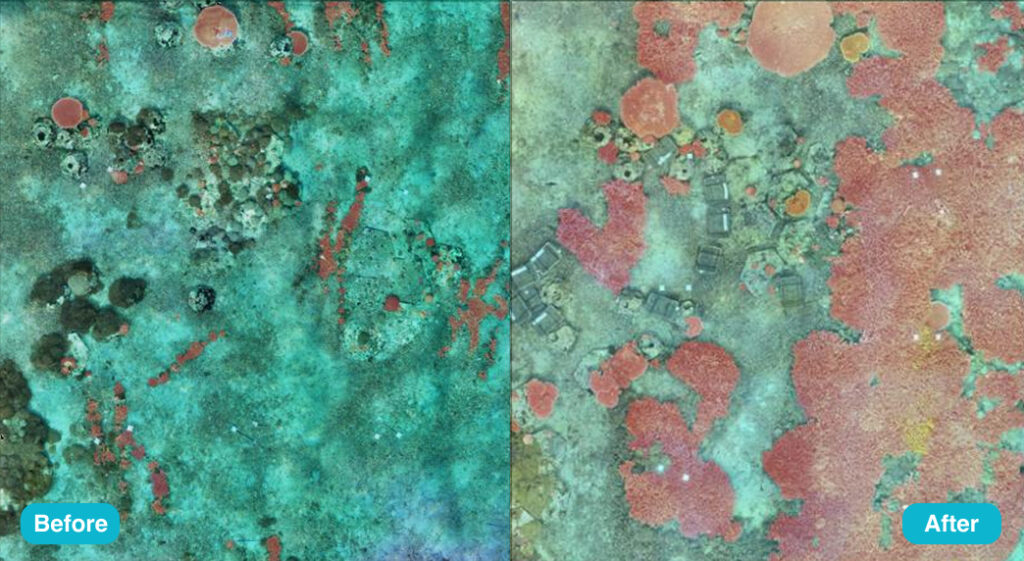

Three years ago, the seafloor at our Sea Trees site in PED was almost completely bare. What should have been a living coral reef had been reduced to rubble, offering little shelter for fish or other marine life. Today, that same patch of reef tells a very different story. Since beginning restoration work, we have increased hard coral cover from less than 5% of the available area to over 52% and the reef is still growing.

Sea Trees is just one small part of a much larger area that was heavily degraded, but the recovery we see here reflects a broader change happening across PED. It shows what is possible when coral restoration is thoughtfully designed and focused on simple, effective solutions.

Before restoration began, a large pontoon was anchored at the site. Over time, hanging mooring lines and poor snorkelling practices had caused extensive damage to the surrounding reef. Corals were broken apart, the reef structure collapsed, and what remained was a wide patch of unstable rubble. Once damage like this occurs, reefs often struggle to recover on their own.

In healthy conditions, coral reefs can regenerate naturally. But on damaged sites like this, recovery is extremely slow. Hard corals grow slowly and need stable surfaces to settle and survive. Without that stability, they are often buried and quickly overgrown by algae or soft corals, leading to long-term shifts away from the vibrant, fish-rich reefs people recognise.

Working closely with the local community and using low-tech, low-cost restoration methods, we began rebuilding the reef from the ground up. Our efforts focus on the fast-growing coral genus Acropora, which forms the backbone of healthy shallow reefs around Penida.

You can still find thriving Acropora colonies along parts of the coastline that have remained relatively undisturbed. These natural reefs guided our restoration design. Instead of trying to reinvent the reef, we aimed to copy what already works in nature.

To do this, we grow coral fragments in our on-site nursery and then outplant them onto the reef in 2 x 2 metre plots. Each plot contains 60 coral fragments, all from the same species or parent colony. The fragments are suspended from ropes attached to wooden stakes, keeping them off the seafloor where they would otherwise be buried by rubble or overgrown by soft corals. Over time, the fragments grow, branch, and fuse together, forming a single, stable coral structure — much like a natural reef colony.

As coral cover increases, so does habitat complexity. Fish return, invertebrates move in, and the reef begins to function as an ecosystem again.

Looking ahead, our work at PED is far from finished. We continue to monitor coral growth, expand restored areas, remove predators, and refine our methods to improve long-term success. The PED site is also home to our coral nursery, where we are growing temperature-resilient corals which we use for restoration. Alongside this, we have begun reintroducing giant clams and stabilising steeper sections of the reef slope to support broader ecosystem recovery.

Projects like this show what is possible. By understanding the local environment, choosing the right sites, and working hand-in-hand with the community, restoration does not have to be expensive or complicated. Simple, well-designed approaches can make a real difference—bringing damaged reefs back to life.